Probability is used (and misused) in amazingly diverse ways. We might ask for the probability that:

it rains tomorrow, or an earthquake strikes,

a lottery ticket hits big, or a poker hand wins,

an atom decays, or an electron tunnels and flips a computer bit,

the stock market crashes, or a stock doubles in value,

a political candidate wins an election, or a poll returns a spurious result,

a medical test returns a true detection, or a recommended vaccine is safe,

an image contains a pedestrian and the pedestrian is waiting to cross the road, or that the last three letters in this list are etc.

To study probability we will need an equally flexible language that can sensibly discuss electrons, policitians, stock prices, and word prediction.

Outcomes and Outcome Spaces¶

Any random process or experiment produces outcomes that cannot be predicted from information that is available before the outcome occurs. We will use the following language to describe the possible outcomes of a random process:

If we want to define a set by listing its entries, we use curly braces, , and use commas to separate distinct elements of the set. For instance, if , then where is the possible outcome. The order of the elements in the list does not matter.

Examples

For example:

If I flip a coin, then:

the possible outcomes are , .

The outcome space, , is the list of possible sides, .

The size of the outcome space is since the die can land on six different sides.

If I flip two coins, then:

the possible outcomes are , , and so on.

The outcome space, , is the list of possible ordered pairs of tosses, . Notice that this list includes and as distinct outcomes. This means that we pay attention to the order of the tosses.

The size of the outcome space is since there are two possible options for each coin. If ignore the order of the tosses, as when we cannot distinguish the coins, then has only three possible outcomes, 2 heads, 1 head, or no heads.

If I roll a six sided die, then:

the possible outcomes are , , and so on.

The outcome space, , is the list of possible rolls of the die, .

The size of the outcome space is since the die can land on six different sides.

Sets and Subsets¶

Sets can contain smaller sets. For instance, the set contains the smaller set . It is common to denote sets contained in the outcome space with capital letters, e.g. . We use the symbol to show that an element is contained in a set. For instance, .

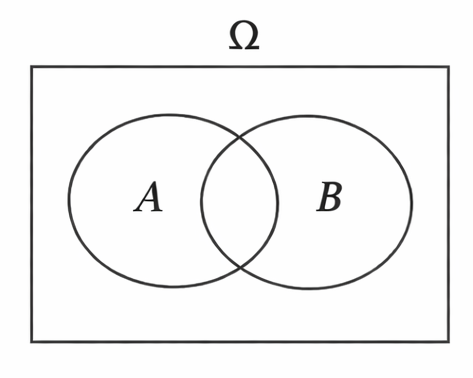

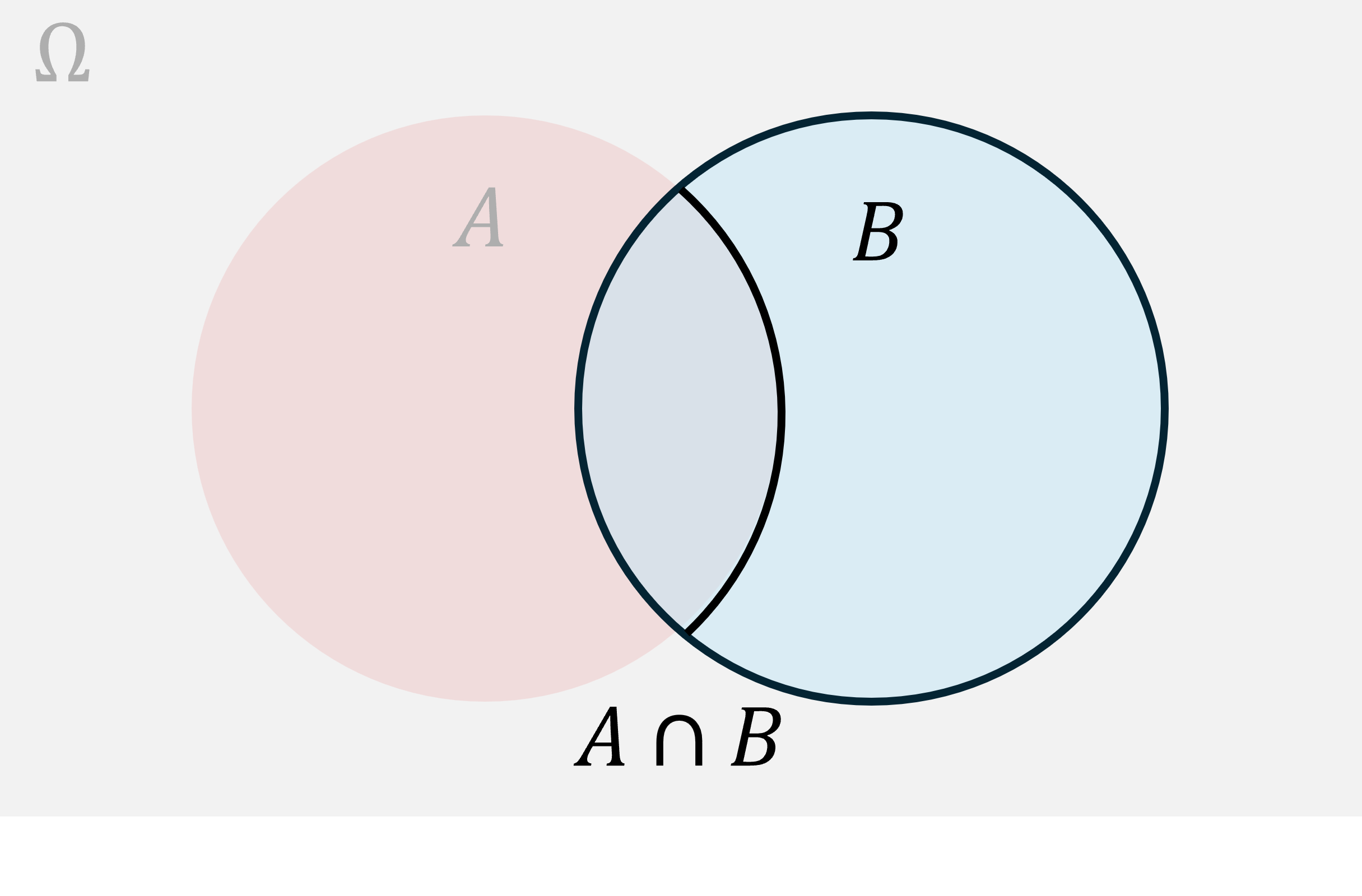

Now that we have multiple sets, we can start comparing their entries. It is standard practice to start from a Venn diagram:

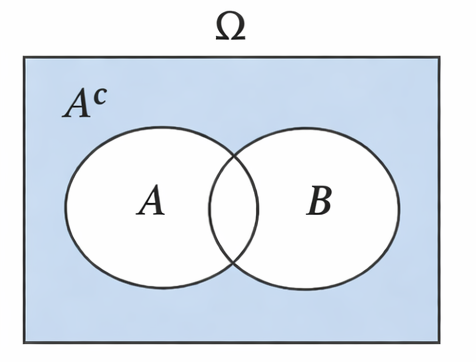

Every set of outcomes is a subset of the outcome space . Every set of outcomes, , divides into two disjoint parts since every element of is either in , or not in . We let denote the complement of . This is collection of all outcomes in that are not in . Any collection of disjoint sets that break a larger set into disjoint pieces is a partition of the larger set. For instance, the pair is a partition of .

If , then is empty, since every outcome is in . The empty set is the opposite of . It contains no outcomes. The empty set is given the special symbol .

Events¶

Sets can be defined explicitly by listing their entries. Sets can also be defined implicitly by introducing a list of conditions that, if satisfied, gaurantee that an outcome is contained in the set.

The relationship between a condition (or list of conditions) on outcomes, and a collection of outcomes that satisfy the condition, is the first key idea in probability. It relates natural language descriptions of events to precise collections of outcomes.

Any time we go to ask a question of the form, “What is the probability that ...” or “What is the chance that ...” we will need to replace the ellipsis (...) with an event. For instance, “What is the probability that the sum of two die add to an even value?” or “What is the probability that a randomly sampled student is a Data Science major and is pursuing a double major in Economics or Engineering?”

If we randomly poll a student and the student:

is a Data Science major, and

is pursuing a double major, and

their double major is either in Economics or Engineering

then the event whose chance we were interested in has occured.

Every event is a list of conditions on outcomes. So, every time we ask “What is the probability that some event occurs?” We are really asking, “What is the probability that the outcome of this random process satisfies the conditions that define the event?” Since every list of conditions defines a set, , “What is the probability that the outcome of this random process is contained in the set ?”

In notation, we could express this question “What is ?” or, in standard shorthand, “What is ?”

These observations suggest the following definition:

Many probability questions can be expressed simply, “Find .” We will focus about a third of our effort in this class to this problem, i.e. to computing chances.

Example: Permutations¶

The following example is adapted from the Data 140 textbook.

Suppose you are shuffling three cards labeled , , and . Then the space of all possible outcomes is

The event can be described as “ appears first or last”. 🛠️ Try filling in the events in the table below:

| Event | Verbal Description | Subset |

|---|---|---|

| appears first | ||

| and are next to each other | ||

| the letters are in reverse alphabetical order | ||

| does not appear | ||

| is either first, second, or third | ||

| the letters form a word that means ‘taxi’ |

Answers

| Event | Verbal Description | Subset |

|---|---|---|

| appears first | ||

| and are next to each other | ||

| the letters are in reverse alphabetical order | ||

| does not appear | ||

| is either first, second, or third | ||

| the letters form a word that means ‘taxi’ |

Notice that we can describe events that contain every possible outcome. Then the event equals .

We can also describe events that are impossible. If an event is impossible then no outcome satisfies the event, so the corresponding set is empty. Hence, in the table above.

Combining Events¶

We will often define events as combinations of other events. For instance, we might be interested in the event that a randomly sampled student is either a sophomore or junior. This event concatenates the events, the student is a sophomore, and the event, the student is a junior. Formally, we combine events by listing the constraints that define each component of the event, then rules for combining those constraints. These rules can be boiled down to four logical operations:

not: e.g. event does not happen. Applying “not” replaces with its complement, .

So, every time you see (or think) the word not you should consider the event’s complement.

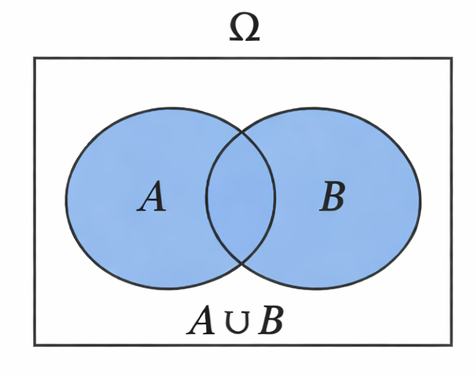

or: e.g. either event happens or event happens. Applying “or” combines all the outcomes contained in the collections and .

For instance, the set of die rolls that are either even or less than 4 is the set . Notice that we never list an identical outcome twice. This set is produced by listing all the distinct entries that appear in or .

The set operation that corresponds to or is a union, denoted . For instance, if and then . You should read as “ union ”. Like in a good marriage, the union of two sets is the collection of all entries owned by both sets.

Notice: combining sets with the contraction “or” never makes the sets smaller. If they are distinct, it makes the sets larger. So, adding an “or” statement makes an event more general. The more ways an event can occur, the more likely it is. So, expanding an event with an “or” statements never decreases its chance.

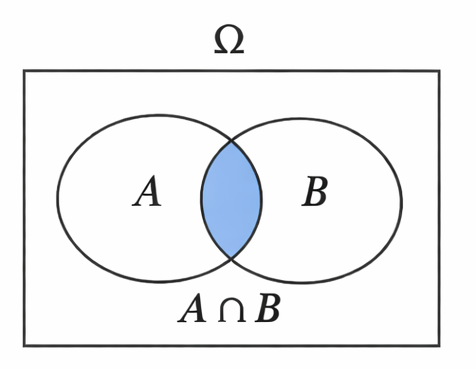

and: e.g. event happens and event happens. Applying “and” restricts our attention to only the outcomes that are contained in both sets. These are the outcomes that satisfy all of the conditions in and . For instance, the set of all die rolls that are even and are less than 4 is the set .

The set operation that corresponds to and is a intersection, denoted . For instance, if and then . You should read as “ intersect ”.

Notice: combining sets with the contraction “and” never makes the sets larger. It usually makes the sets smaller. So, adding an “and” statement makes an event more specific. Contracting an event with an “and” statements never increases its chance.

if: e.g. what is the probability that event happens if event happens? Applying if restricts the outcome space. If happens, then any outcome cannot happen. So, since we don’t need to consider impossible events when computing chances, we can replace with .

Restricting the outcome space to all outcomes that satisfy an if statement is called conditioning.

For instance, the probability that a die roll is less than 4 if the roll is even should be computed using the outcome space .

It is common to use “given that” instead of “if”. For instance, the statements, “Find the probability that a die roll is less than 4 if it is even” is the same as the statement “Find the probability that a die roll is less than 4 given that the roll is even.”

The standard notation for “if” is a vertical bar. E.g. means, “the probability that happens if happens”.

Solution

Here’s a reasonable diagram:

We’ve grayed out all of and outside of since, when we condition on , we are restricting our attention to . Then, the set represents the only outcomes where happens, given that we start in . Notice that the definition of the event is the same as for and. What’s changed is the outcome space. Instead of looking at the intersection relative to all of , we are only comparing it to . We’ll see in Section 1.5 that the formula for conditional chances looks like the formula for joint chances (and statements), but rescaled so that proportions are evaluated out of the event we condition on () instead of .

In summary:

P.S. A Comment on Notation¶

We introduced a lot of notation in this section. Notation is crucial in mathematics since abstract notation can express a general idea that is realized in many different specific ways. For instance, means the probability of the event , which can serve as shorthand for any of the probabilities listed at the start of the chapter. We could let stand for “it rains tomorrow” or “this stock doubles in value in the next quarter” without changing the notation used for the probability of an event. Compressing many different statements with an abstract shorthand is powerful since it will allow us to prove common facts about apparently unrelated systems. It will also allow us to say complicated things quickly.

Notation is also intimidating and exclusionary. Like any language, it is foreign on first exposure, and can seem more like a special code, or pedant’s jargon. We will do our best to avoid unneeded notation and to explain every notation introduced. In exchange, we promise that the notation we do use is worth learning, and expect you to learn it.

If you struggle with new notation, or found the notation above opaque, be proactive, and treat it like you would a foreign language. Make a table, with symbols on one side, name each symbol, then add a plain language description of each symbol or notation. It can help to write out a long form explanation, then a concise, pithy, “key” that you use to express the essence of the idea. Try to make the “key” memorable.

Many ideas in set theory are best represented visually with a Venn diagram. So, try drawing a Venn diagram for the cases , , , and and disjoint. Make space in your table for these visuals. You’ll rehearse these skills in your first discussion section.